'Enemy aliens'

The treatment of people of enemy-origin in WWI NSWWho were enemy aliens?

The term ‘alien’ commonly applied to any person who came to New South Wales from a country outside the British Empire (including even the United States of America). After having resided in NSW for a minimum of five years, these people could obtain the privileges and rights of citizenship held by ‘British subjects’ (e.g. voting, owning land) by becoming naturalised. From 1904, this involved applying to the Commonwealth Government of Australia and, upon approval, swearing an oath of allegiance to the King who during the war was George V.

The majority of enemy aliens were of German-origin. An average of 190 Germans and 23 Austrians were becoming naturalised each year in the five years leading up to the war (1909-1913), and in the year the war began (1914) these figures increased to 596 Germans and 64 Austrians being naturalised.[2] It is likely that the majority of these occurred in the rush of applications during the first five months of the war between, August and December 1914.[3]

Pre-war German-Australian relations

German immigration had been strong (compared to other non-British nationalities) since the assisted immigration schemes of the late 1840s,[4] and the census of 1911 reveals that there were more than 33,000 people of German-birth living in Australia before the war.[5] Taking into account the official Lutheran church member figures for the time, there was probably almost 100,000 people with recent German heritage resident in the country, including second and third generation descendants of German immigrants.[6] German communities developed in NSW, particularly in rural areas such as the Riverina area close to the Victorian border. German immigrants also found work in cities, established businesses, and started families – often with Australian-born wives. By 1914, many German immigrants had been living in Australia for decades.

Up until that year, Germany and Australia enjoyed a strong trade relationship, in which Germany was purchasing twice as much as she sold to Australia.[7] Our wool and mining products were the highest exported goods to Germany,[8] and overall 12% of NSW exports during 1913 went to countries who became enemies of the Commonwealth the following year.[9]

Early attitudes of NSW public and Government

At the onset of war in early August 1914, many members of the public expressed the need for the fair treatment of German-Australians.[10] Local newspapers, particularly in rural areas, published articles urging British subjects to treat ‘Germans in their midst’ with humanity and consideration, given the crisis. The Sydney Morning Herald, for example, published an appeal urging the public not to allow racial hatred to grow “in the next few weeks”,[11] (which also reveals the belief at the time of the probability of a short war):

“Treat them with the consideration due to the misfortunes of a friend…see that… their nationality does not bring them discomfort or ill-treatment.”

In the NSW Parliament, both Government and Opposition pledged to preserve courtesy to naturalised and unnaturalised Germans, as well as people of German descent. Premier Holman stated on 5 August 1914, that:

“The rupture of the friendly relations between the two nations has in no way altered the sentiment which Australia as a whole entertains towards the Germans in our midst…throughout all these difficulties those fellow-residents of ours will continue to learn by experience what Australian hospitality means.”[12]

- Premier William Holman. From NRS 4481, ST13302

- Opposition Leader, Charles Gregory Wade. From NRS 4481, ST28786

On the same day NSW opposition leader, Charles Gregory Wade, mirrored the Premier’s sentiment in saying:

“There are many [unnaturalised] men in this community who, though German, are personal friends of British citizens, and who can in no way be held responsible for the present crisis…

…although we are out to fight the nations who challenge us, we cannot forget the bonds of friendship.”[13]

From 10 August 1914, a Federal Government proclamation was released, requiring all subjects of the German Empire to report to their nearest police station and provide personal details,[14] including address and occupation or businesses, and to thereafter notify the Police of any change to these details.[15] Four days later the same was required of those born in Austria-Hungary.[16]

- List of enemy reporting at police stations, form, June 1915. From NRS 10929, [7/6187]

- Manual of War Precautions, Second Edition’, 4/8/1915. From NRS 12060, [9/4745], A17/4293

This was followed by the War Precautions Act, introduced on 29 October 1914 to allow the Commonwealth Government to utilise public and private spaces as well as property to assist in the war effort; but also to control those that it deemed may be a threat to security. It potentially applied to all Australian residents, but was largely aimed at enemy aliens and naturalised persons alike, should suspicion be raised of ‘disloyal’ activity, for example.

The Act’s regulations broadened over the course of the war to mean that enemy aliens could not travel interstate or overseas without permission from the Military, nor keep motor vehicles, cameras, telephones, most firearms, or even flammable liquids.[17] Communication both overseas and locally was also restricted. Any breach of these regulations presented the threat of imprisonment (in internment in camps like those at Trial Bay and Holsworthy) and/or deportation. Whether a person was deemed to be a threat was essentially up to the discretion of the military, whether a breach had clearly occurred or not. The accused were not offered legal representation, nor were trials conducted to decide if a person was innocent or guilty.[18]

A turning point

The tone of discussions both in public and in Parliament, began to change as early as September 1914. During that month, newspapers reported on ‘German atrocities’ allegedly committed by German soldiers in Belgium,[19] as well as the first Australian casualties during the Battle of Bita Paka in (then) German New Guinea.[20]

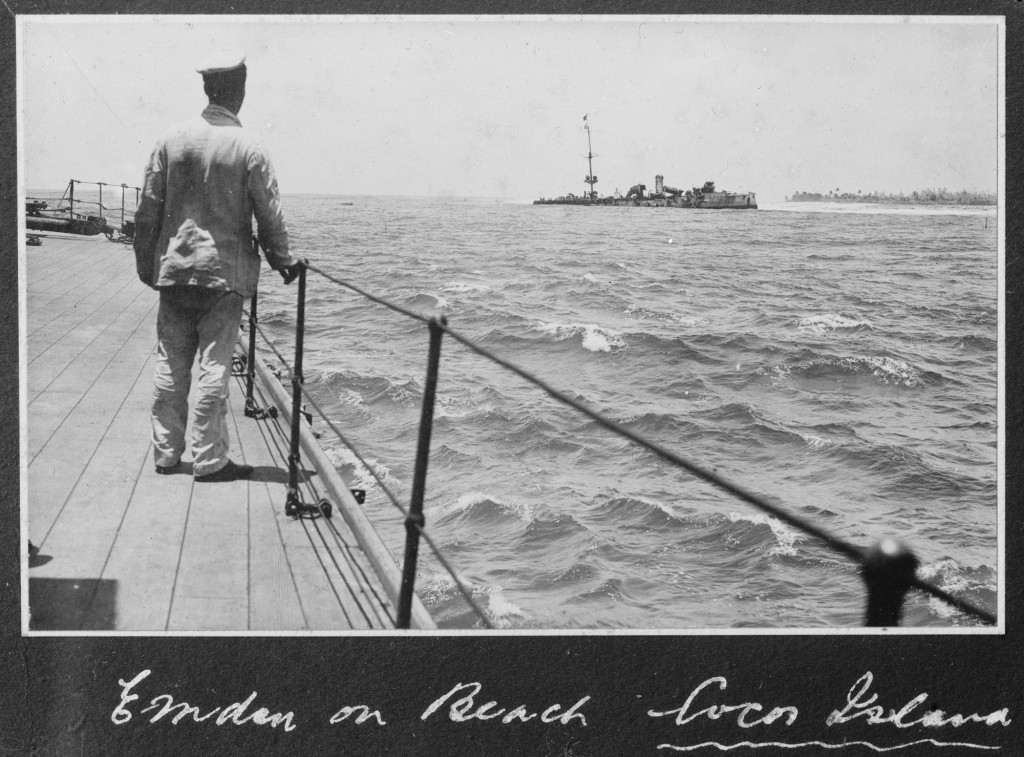

By November 1914, questions were being raised in the NSW Parliament about ‘Germans’ in the NSW public service,[21] while the first major Australian victory occurred when the HMAS Sydney sank the German ship Emden.[22] At the same time, an ‘Anti-German League’ was formed in Victoria,[23] as well as the first internment under the War Precautions Act,[24] which had been assented to on 29 October.

Public opinion of people of enemy origins (including people suspected of being of German heritage) changed drastically over April-May 1915, after a series of events tipped already simmering tensions within the community to boiling point. They were:

- The gassing of allied forces by Germans at Ypres in late April 1915 [25]

- The first major military engagement of Australian forces occurred with the landing of the ANZACs at Gallipoli on 25 April, with the first casualty lists being printed in Australia in early May [26]

- A German submarine torpedoed and sank the passenger liner Lusitania on 7 May with a loss of more than 1,500 lives [27]

- Finally the ‘Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages’, or ‘Bryce Report’ was released and distributed widely during May, and was particularly damaging in its allegations of acts of brutality and cruelty committed by the German forces [28]

From this point, anti-German sentiment intensified throughout Australia.[29] It took various forms, such as anti-German letters being published in newspapers, along with calls for anti-German leagues to be formed and the boycotting of all German products – even names of people suspected of being enemy aliens were published.[30] General anti-German propaganda material also began to be distributed, not only by members of the public, but by governments as well.[31] This attitude was not aimed only at the German military or its leaders fighting the war in Europe, but at anyone or anything German in Australia.

![The Call to Arms, Number 8, p. 13. From NRS 12060 [9/4732] B16/1725](http://nswanzaccentenary.records.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/NRS120609-4732B16-1725A_Call-to-arms_p13-300x204.jpg)

The Call to Arms, Number 8, p. 13. From NRS 12060 [9/4732] B16/1725

Some citizens of German heritage (even those born in Australia) felt the need to change their name, often to an ‘anglicised’ variation,[37] and several New South Wales towns adopted new names during the war.[38] The experiences of many people of enemy country origin and heritage reveal a different perspective of the difficulties of life in WWI Australia. Many of these stories can be found in NSW State Archives.

References

[1] NSW Migration Heritage Centre. (2011). The Enemy at Home: German Internees in World War I Australia – The Camps and the System of Internment (web page). Retrieved from http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/enemyathome/the-camps-and-the-system-of-internment/index.html. [2] Parliamentary Papers, 1915-1916, Vol. 1, ‘Germans and Austrians within the Commonwealth’. [3] Scott, Ernest, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918: Volume XI Australia During the War, 1936, p. 108. [4] State Archives New South Wales, Archives in Brief 50 – German migration and settlement in New South Wales, 2003. [5] McKernan, Michael, The Australian people and the Great War, Sydney, William Collins Pty Ltd, 1980, p.150. [6] Fischer, Gerhard, Enemy Aliens: Internment and the Homefront Experience in Australia, 1914-1920, University of Queensland Press, 1989, p. 15; Williams, J F, German Anzacs and the First World War, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, 1983, p. 18. [7] SANSW: NRS 12060, [9/4687], 14/1459, ‘Trade During the Year 1912 Between Germany and the Commonwealth of Australia & Between Germany and the British Isles’, p. 2. [8] NRS 12060, [9/4687], 14/1459, ‘Trade During the Year 1912 Between Germany and the Commonwealth of Australia & Between Germany and the British Isles’, p. 1. [9] NRS 12060, [9/4697], 15/1430. [10] Fischer, p. 15; Williams, pp. 36-38. [11] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 August 1914, p. 8. [12] New South Wales Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Vol. 55, 5 August 1914, Questions and Answers, ‘Courtesy to German Citizens’, p. 588. [13] New South Wales Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Vol. 55, 5 August 1914, Questions and Answers, ‘Courtesy to German Citizens’, p. 588. [14] SANSW: NRS 10929, Copies of circulars, memoranda and circular memoranda sent, Police Department, 1913-1915, 7/6187, Circular Memo. 776, 11/8/1914. [15] Fischer, G & Helmi, N, The Enemy at Home: German Internees in World War I Australia, Historic House Trust of NSW, UNSW Press, 2011, p. 20. [16] NRS 10929, 7/6187, Circular Memo. 802, 14/8/1914. [17] NRS 12060, [9/4745], A17/4293, enclosing ‘Manual of War Precautions, Second Edition’, 4/8/1915. [18] Fischer, p. 66. [19] The Farmer and Settler, 10 September 1914, p. 1. [20] Evening News, 12 September 1914, p. 1. [21] Nepean Times, 7 November 1914, p. 3. [22] Bean, C. E. W., ‘Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Volume I The Story of Anzac: The First Phase’, 1942; p. 106. [23] The Bathurst Times, 2 November 1914, p. 1. [24] The Independent (Deniliquin), 20 November 1914, p. 2. [25] Williams, pp. 49-50. [26] Selleck, R. J. W, ‘The trouble with my looking glass’: a study of the attitude of Australians to Germans during the Great War, p. 4 (Presidential address to Australian and New Zealand History of Education Society, Annual Conference, Trinity College, Melbourne, August 1979), in Journal of Australian Studies, (6), 2-25. [27] Ibid, pp. 3-4. [28] Williams, pp. 49-50. [29] Fischer, p. 124. [30] Ibid. [31] See examples in: The Call to Arms, Number 8, 25 April 1916; The Truth About German Atrocities. [32] The Australian Worker, 27/5/1915, ‘Enemy Aliens: The Question of Internment’, p. 18. [33] Parliamentary Papers, 1915-16, V5, pp. 787-788, ‘Petition from Certain Citizens of New South Wales, Regarding the Holding of Citizens’ Rights and Positions in the Public Service by Persons of Enemy Origin’, 14/12/1915; Parliamentary Papers, 1915-16, Vol. 5, p. 789, ‘Petition from E S Sautelle, Mayor of Vaucluse, and Certain Residents of New South Wales, Regarding the Holding of Citizens’ Rights and Positions in the Public Service by Persons of Enemy Origin’, 16/11/1915. [34] NRS 12060, [9/4707], 15/8056. [35] Sunday Times, 29/8/1915, p. 2, for example. [36] New South Wales Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Vol. 56, 11/11/1914, p. 1079, ‘Germans in the Public Service/Foreign Flags’. [37] (For example, in the case of Ernest Ludwig Schultz, later Ernest McBryde) NRS 7953, [22/4367], 10/13990, enclosing 15/57496, 20/9/1915. [38] German Creek (later Empire Vale), NRS 3828, Department of Public Instruction, Indexes and registers of letters received [Correspondence Branch], 6/382, p. 50; Germanton (later Holbrook), NRS 3828, 6/382, p. 52; German’s Hill (later Lidster), NRS 3828, 6/382, p. 51.

![List of enemy reporting at police stations, form, June 1915. From NRS 10929, [7/6187]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/NRS109297-6187_011-150x150.jpg)

![Manual of War Precautions, Second Edition’, 4/8/1915. From NRS 12060, [9/4745], A17/4293](/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/NRS120609-4745A17-4293_War-precautions-150x150.jpg)