Military exemption courts

The running of the exemption courtsGrounds for exemption: exempted professions and industries

Applications for an exemption from military service generally fell into two classes. The first class or group of people who could apply for an exemption were covered under Section 61 of the Defence Act 1903. (1) This group included:

- Men deemed medically unfit due to a mental or physical disability;

- Members or Officers of State or Commonwealth Governments;

- Judges and magistrates;

- Ministers of religion or those studying to join a religious order or devoted to full-time duties;

- Conscientious objectors.

The local exemption court had no discretion with the applications in this specified class and had to approve the exemption. The list was expanded to include those employed in the police or gaol service, doctors and nurses in public health care, lighthouse keepers, persons who were not substantially of European descent or people employed in protected industries. (2)

Protected industries

On 25 October 1915 the Industries Exemption Advisory Committee issued recommendations on protected industries. People working in these industries, depending on their work role, could apply for absolute exemptions or temporary exemptions which would be regularly reviewed. The protected industries included of customs and shipping clerks, crews of shipping vessels, dental students, agricultural workers and sheep shearers and workers in copper and lead mines, refineries, iron and steel rolling mills. Other protected industries included chemical manufacturers, engineering and boiler making, iron, steel and brass foundries, rope and cordage manufacturers and sail, tent and tarpaulin makers. (3)

Government departments and private firms could also apply for exemptions for their employees. Private firms not already covered as protected industries, could apply for up to 12 exemptions for work of national importance being performed or specialist work that could not be performed by another person or a returned or discharged soldier. (4)

Early in October 1916 Premier Holman held a meeting with representatives of the New South Wales Public Service to decide which sectors of the public service would be exempt from the call up. It was decided that the Railways, Police, Justice Department (Courts of Petty Sessions [Fig. 1]), Public Instruction Department and the Sydney Harbour Trust had special need for exemptions. Applications could be made in bulk for each department but were limited to as few men as necessary. (5)

- [Fig. 1] List of officers in Petty Sessions. From NRS 324 [7/5514 letter 17/13187].

- [Fig. 2] Brodie declared unfit by military, November 1917. From NRS 324 [7/5514 letter 17/13187].

- [Fig. 3] Brodie on exemption list, November 1916. From NRS 324 [7/5514 letter 17/13187].

The case of George Beresford Brodie, an assistant clerk in the Court of Petty Sessions at Wagga Wagga, reveals how feelings about conscription were running high. [Fig. 2-3] It appears the Justice Department included Brodie on a list of public servants they wanted an exemption for in October 1916. (6) Brodie, feeling aggrieved that he was on the exemption list, wrote to the Under Secretary in the Department of Attorney General and Justice to explain that he had not personally requested an exemption. In fact Brodie had already offered his service to the Australian Imperial Force and been rejected as being unfit. (7)

Grounds for exemption: family circumstances

The second class or group who could apply for exemptions fell under Division 3 of the War Service Regulations. This group could apply for an exemption on grounds of expediency or domestic financial obligations. It included men who were the “sole remaining son or one of the remaining sons of a family of whose sons one-half at least have enlisted” or “sole support of aged parents, or widowed mother, or orphan brothers and sisters under the age of sixteen

years”. (8) The court had discretionary powers, based on the evidence provided, including calling witnesses and demanding statutory declarations to refuse or grant an exemption application.

One of the problems of the military exemption court was that many of the legal terms that the judges were meant to make ruling on were not defined. These terms included “employed in the national interest”, “exceptional domestic financial obligations” and “only son”. (9) This led to different interpretations by the various judges.

- [Fig. 4] Letter to Attorney General from Latimer. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/14973, p.1]

- [Fig. 5] Letter to Attorney General from Latimer. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/14973, p.2]

- [Fig. 6] Letter to Attorney General from Latimer. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/14973, p.3]

- [Fig. 7] Letter to Attorney General from Latimer. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/14973, p.4]

One case that highlighted this problem was that of JRW Bellhouse, of Woollahra, Sydney. [Fig. 4-7] Bellhouse had applied for an exemption as an only son in October 1916 and his case was heard in the Paddington Police Court. Bellhouse’s exemption was refused by the judge, even though his 78 year old grandmother testified that Bellhouse’s parents were both dead and he was the only issue from the marriage. Attention was brought to the case when William Fleming Latimer, the Member for Woollahra, wrote to the NSW Attorney General asking for the magistrate’s ‘inexplicable’ decision to be reviewed. His request was forwarded to the Commonwealth Military authorities. (10)

The running of the exemption courts

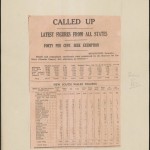

By 22 October 1916, nearly one month after the proclamation calling up single men was issued, 54 581 men [Fig. 13] had reported for military service in NSW. (11) Nearly half of those who reported applied for an exemption (27,074 men) but only 966 cases had been dealt with in the exemption court. Of the 966 cases, 682 exemptions were allowed (71%) and 284 cases were disallowed. (12)

- [Fig. 8] Bribery letter. From NRS 324 [7/5504 letter 16/15172].

- [Fig. 9] Bribery envelope. Bribery letter. From NRS 324 [7/5504 letter 16/15172].

- [Fig. 10] Newspaper cutting and Allnutt notes. Bribery letter. From NRS 324 [7/5504 letter 16/15172, p.1].

- [Fig. 11] Newspaper cutting and Allnutt notes. Bribery letter. From NRS 324 [7/5504 letter 16/15172, p.2].

- [Fig. 12] Police report. Newspaper cutting and Allnutt notes. Bribery letter. From NRS 324 [7/5504 letter 16/15172].

A curious case of bribery arose in Singleton in November 1916. Police Magistrate Robert Henry Venn Allnutt was sitting in the Military Exemption Court in Singleton when he received an anonymous letter offering him a bribe of 100 pounds in gold if he would grant an exemption to Oliver Robinson. [Fig. 8-9] Allnutt revealed the bribery attempt in court on Thursday 2 November, stating that the offer was an “attempt to divert justice and a personal affront to himself”. (13) The police investigated the bribery attempt, clearing both Oliver and his father, H S Robinson. It turned out there had been several other bribery letters in Singleton in the previous few months. [Fig 1-12]

- [Fig. 13] Called Up, The Sunday Times, 22 October 1916. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1].

- [Fig. 14] Abandon military exemption court proceedings, 22 November 1916. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/15972].

- [Fig. 15] Cost of services of Henry Sydney Beveridge, Clerk of Petty Sessions. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 16/16834].

- [Fig. 16] Statement of costs for NSW exemption courts, January 1917. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1].

- [Fig. 17] Request for records of military exemption court, 1920. From NRS 333 [3/3063.1 letter 20/12782]

On 23 November 1916 Prime Minister Hughes announced that, in the wake of the defeat of the conscription plebiscite, the military exemption courts would close. (14)[Fig. 14] In January 1917 the NSW Justice Department issued an invoice for £850 to the Commonwealth Government [Fig. 16], to cover the cost of running the exemption courts in the state. (15) An individual statement from Henry Sydney Beveridge, a petty sessions clerk at Burwood Court, itemised the work he had undertaken in the military exemption court from 6 to 31 October 1916. [Fig. 15] He worked just over 57 hours at a cost of 3 shillings and 11 pence per hour, with the total cost of his services being £11 4 shillings and 2 pence. (16)

Very few records of the local military exemption courts in New South Wales have survived. On 29 September 1920 a circular was sent to all clerks of Petty Sessions throughout NSW asking them to hand over records of the exemption courts to military authorities. [Fig. 17] Some individual applications made by men employed in the public service have survived in the papers of the Chief Secretary and in a series of records from the Bowral Local Military Exemption Court.

Related

References

(1) Commonwealth Consolidated Acts, Defence Act 1903, Section 61A: Persons exempt from service, http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/da190356/s61a.html, accessed 22 June 2015.

(2) Scott,Ernest, “Chapter IX: First Conscription Referendum”, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Vol. XI, 7th Ed., 1941, Sydney, Angus & Robertson, p.350.

(3) ‘Called up: List of exemptions to help industries’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 October 1916, p.12, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/15684265; ‘Called up: More exemptions issued”, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 1916, p.6, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/15686040.

(4) State Archives New South Wales: Attorney General’s Department; NRS 333 Letters received – Special bundles, [3/3063.1] War Service Regulations 1916 (Statutory Rules 1916. No. 240), #46.

(5) ‘Civil service exemptions’, Daily Telegraph, 9 October 1916, in NRS 333, [3/3063.1].

(6) SANSW: Department of Attorney General and Justice; NRS 324 Letters received, [7/5514] 17/13187.

(7) Ibid.

(8) NRS 333 [3/3063.1] War Service Regulations 1916 (Statutory Rules 1916. No. 240), #35.

(9) Ibid.

(10) NRS 333 [3/3063.1] 16/14973.

(11) NRS 333 [3/3063.1] ‘Called up’, Sunday Times 22 October 1916.

(12) Ibid.

(13) NRS 324 Letters received, [7/5504] 16/15172.

(14) NRS 333, [3/3063.1] 16/15972.

(15) NRS 333, [3/3063.1] 16/16834.

(16) Ibid.