The first Anzac Day

25 April 1916

Anzac Day as a country-wide event appears to have been proposed by the Queensland State Government to Premier Holman and other premiers [see Fig 2],[5] and although 25 April 1916 fell on a Tuesday, the state governments decided it was inappropriate to declare it a public holiday.[6] In fact, Victoria at first thought it premature to arrange a ‘special day’ in recognition of the Australian soldiers, in the perceived probability that the Australian Imperial Force would further “distinguish themselves” during the course of the war. Tasmania initially felt it was inappropriate to appear to celebrate a campaign they believed “must for all time be regarded as a failure” for the blameless Australian forces [see Fig 3].[7] In the end, individual states decided how and to what extent their commemorations were to be held.[8]

- Fig 2: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475, enclosing A16/585

- Fig 3: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475 enclosing A16/1482

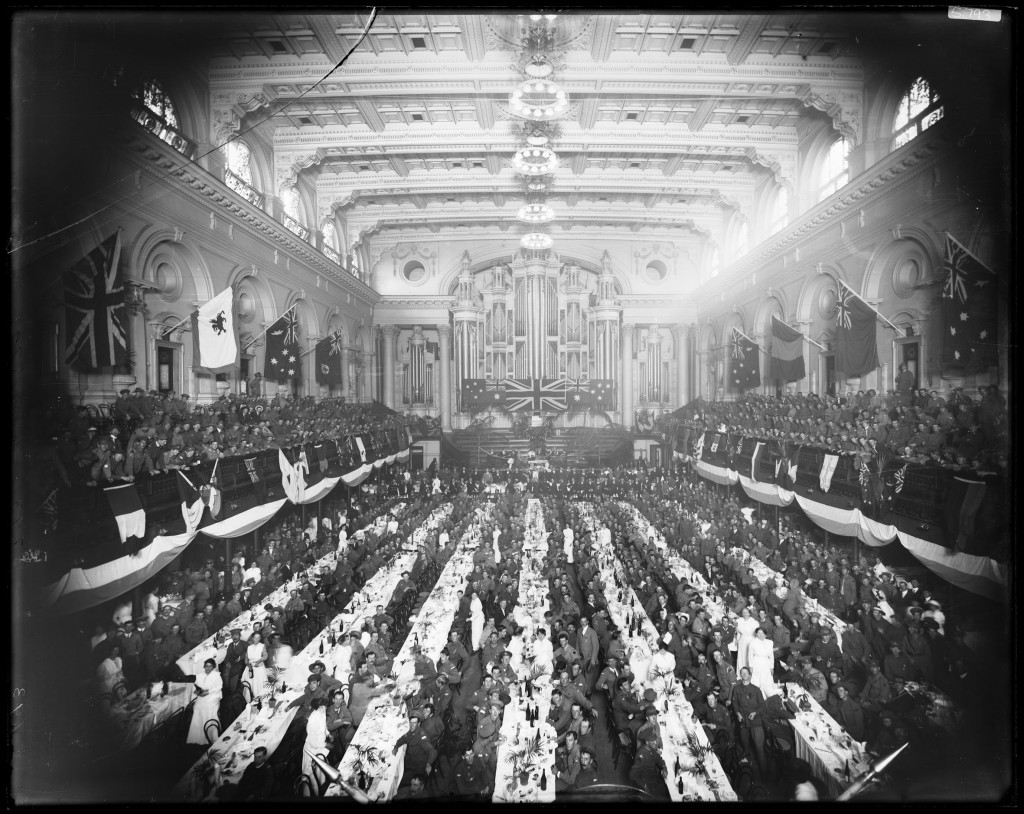

While the NSW Government wanted to “commemorate the glorious landing of Australia’s sons at Anzac”, it also saw an opportunity to encourage recruitment and fundraising. [Fig 1].[9] The Returned Services Association (of which Premier Holman was president) also sought to utilise the commemoration to raise funds through the ‘Anzac Day Fund’, to build an ‘Anzac Memorial Hall’ adorned with the names of the fallen,[10] despite a promise made by the Premier not to allow collections on the day.[11]

At the time it was believed that church services should be central to the day’s events. [12] Premier Holman personally requested State-wide memorial services to recognise:

“the glorious part played by Australian soldiers in their baptism of fire, the remembrance of the many graves in enemy territory and the presence amongst us of the sick and wounded heroes of the fight”.[13]

- Fig 4: The King’s Anzac Day message. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]

- Fig 5: Message from the King, The Daily Telegraph , 24/4/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]

- Fig 6: Official correction to message from the King, The Sun , 25/4/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]

- Fig 7: Governor Strickland’s letter to the Governor General, 26/5/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]

An unexpected disagreement between the Australian Governor-General, Sir Ronald Craufurd Munro Ferguson and the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Gerald Strickland occurred in relation to Anzac Day. Strickland had the King’s message to the Australian people published the day before Anzac Day [see Figs 4; Fig 5], implying that he had been instructed to do so by His Majesty directly.[14] Sir Munro Ferguson took issue with Strickland’s direct communication with the British authorities,[15] and even published a ‘correction’ on Anzac Day itself in Sydney newspapers, undermining Strickland’s announcement of 24 April 1916 [see Fig 6].[16] Strickland defended himself, stating that similar messages had been printed by five of the other state’s Governors [see Fig 7],[17]. He argued that not only were state governors not answerable to the Governor General, but that Munro Ferguson’s “attack on the accuracy of a State Governor in the press” was unprecedented, especially without an explanation having been sought first by the Governor-General before doing so.[18] The disagreement is said to have continued for months.[19]

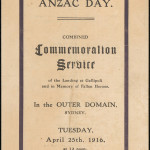

- Fig 8: Anzac Day 1916 Commemoration Service program [cover]. From: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475

- Fig 9: Anzac Day 1916 Commemoration Service program [inside]. From: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475

- Fig 10: Anzac Day 1916 Commemoration Service program [rear]. From: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475

On the first Anzac Day in Sydney, 4,000 returned servicemen (essentially the number of members of the Returned Soldiers’ Association of New South Wales)[20] marched or were driven in cars through the streets following the route: St Mary’s Cathedral Gates, Macquarie Street, Bridge Street, George Street, Liverpool Street, Elizabeth Street, St James Road, back to St Mary’s Cathedral Gates[21] and then to the Domain where 50,000-60,000 people had gathered, despite an earlier shower. As the crowd watched the Gallipoli veterans enter the Outer Domain, the gentle singing en masse of ‘Abide with Me’[22] followed by other stirring tunes, was remembered years later by then Chief Secretary, George Black as one of the most emotional moments of his life.[23] Prayers and scripture were delivered by Reverends William Parson and R Scott West [see Fig 9],[24] before Archbishop John Charles Wright delivered the principal address to the soldiers. The service was concluded with the playing of ‘The Last Post’ and the ‘National Anthem’.[25]

The soldiers then marched to Town Hall for a luncheon and ‘entertainment’,[26] where “not one vacant seat” was to be found on the tables which covered the entire floor of the main hall [Fig 11]. The event was presided over by the Lord Mayor of Sydney and Premier Holman closed the luncheon by asking the men “to drink the toast not only to the memory of the fallen, but to those who were determined to see victory crown their effort”. In keeping with this last point, the afternoon was dedicated to nine recruitment rallies across the city, before the Town Hall was host once more to an evening concert for the Gallipoli veterans.[27]

This first commemoration in 1916 started a tradition that would become increasingly important and popular in the coming years to the people of NSW and Australia.

*Some of the above text and records were originally included in our 2014 exhibition A Call to Arms.

Related

References

[1] Robertson, John, Anzac and Empire, Port Melbourne, Hamlyn Australia, 1990, p. 247. [2] “United Service – A Great Scene”, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1916, p. 11. [3] Robertson, p. 246. [4] “Anzac Day”, The Gloucester Advocate, 22 April 1916, p. 2. [5] Robertson, p. 247; Thomson, Alistair, Anzac Memories: Living with the Legend, South Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 130; State Archives New South Wales: Premier’s Department; NRS 12060 Letters received, [9/4857] B20/2475 enclosing A16/585 Minute ‘First Landing of Australian Troops in Gallipoli – Proposed Anniversary Celebration’, 25/2/1916. [6] NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475, enclosing A16/1482, 24/3/1916; McKernan, Michael, The Australian People and the Great War, Sydney, Collins, 1984, p. 214. [7] NRS 12060 [9/4857] B20/2475, enclosing A16/1482, 24/3/191.6. [8] Robertson, p. 247. [9] NRS 12060 [9/4857] B20/2475, RSA ‘Anzac Day’ letterhead, 8/4/1916. [10] Parliamentary Papers, 1915-16, Vol. 8, p. 924, ‘Anzac Day Collections’, 11/4/ 1916. [11] NRS 12060 [9/4857] B20/2475, enclosing ‘Anzac Day – 25 April, 1916’, points 2 and 3. [12] McKernan, p. 214. [13] NRS 12060 [9/4857] B20/2475, enclosing unnumbered letter to Lt Col J Birkenshaw, 15/4/1916. [14] SANSW: Governor; NRS 4541 Despatches from other Governors, and letters from Consuls and Diplomats, officials and private persons, and copies of letters sent, [7/1668A], enclosing No. 47, 26/5/1916. [15] Robertson, p. 247. [16] NRS 4541 Despatches from other Governors, and letters from Consuls and Diplomats, officials and private persons, and copies of letters sent, [7/1668A]. [17] NRS 4541 Despatches from other Governors, and letters from Consuls and Diplomats, officials and private persons, and copies of letters sent, [7/1668A], enclosing No. 47, 19/5/1916. [18] NRS 4541, Despatches from other Governors, and letters from Consuls and Diplomats, officials and private persons, and copies of letters sent, [7/1668A], enclosing No. 47, 26/5/1916. [19] Robertson, p. 247. [20] Parliamentary Papers, 1915-16, Vol. 8, p. 924, ‘Anzac Day Collections’, 11/4/ 1916. [21] “To-Day’s Commemoration – Parade and Church Services”, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 1916, p. 9. [22] “United Service – A Great Scene”, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1916, p. 11. [23] Robertson, p. 247. [24] NRS 12060 Letters received [9/4857] B20/2475, ‘Anzac Day combined Commemoration Service’ program. [25] “United Service – A Great Scene”, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1916, p. 11. [26] “Town Hall – A Memorable Scene”, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1916, p. 12. [27] “To-Day – Anzac Day”, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 1916, p. 10.

![Fig 1: RSA letterhead 8/4/1916. From: NRS12060, [9/4857], B20/2475](http://nswanzaccentenary.records.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS120609-4857B20-2475_005_cropped.jpg)

![Fig 4: The King's Anzac Day message. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS-4541_7_1668A-Kings-message-150x150.jpg)

![Fig 5: Message from the King, The Daily Telegraph , 24/4/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS-4541_7_1668A-Daily-Telegraph-Kings-message-150x150.jpg)

![Fig 6: Official correction to message from the King, The Sun , 25/4/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS-4541_7_1668A-The-Sun-GGs-correction-150x150.jpg)

![Fig 7: Governor Strickland's letter to the Governor General, 26/5/1916. From NRS 4541, [7/1668A]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS-4541_7_1668A-Strickland-letter-150x150.jpg)

![Fig 9: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475, Anzac Day 1916 Commemoration Service program [inside]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS120609-4857B20-2475_013-150x150.jpg)

![Fig 10: NRS 12060, [9/4857], B20/2475, Anzac Day 1916 Commemoration Service program [rear]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NRS120609-4857B20-2475_014-150x150.jpg)