COMMUNITY MEMORIALS & HONOUR ROLLS

How the people of NSW rememberedThis webpage was developed as part of State Archives’ contribution to History Week 2015.

The departure of men and women from New South Wales communities into war service greatly affected those who were left behind and the lives they led. With the death of so many and their burial abroad, as well as the disfigurement and illness often suffered by who those returned, a deep impression was left upon towns, businesses, and Government departments throughout the State.

In response to this the people and Government of NSW dedicated many memorials, monuments, and honour rolls that initially were largely a display of local pride in those who had served or were serving; but soon came to be used as an instrument for encouragement in the recruitment movement during the war. As the tremendous loss of life built over the course of the conflict, these monuments served to commemorate service and sacrifice, as well as to provide a place of mourning for those in Australia so far from where the fallen lay.

The earliest physical public acknowledgments of those who had enlisted came in the form of honour rolls in print, and on boards or plaques, even before the first large campaign involving Australian troops, Gallipoli, had begun.[1] This format then evolved into the form of war memorials from about April 1916 on.[2]

Records relating to these public displays of remembrance can be found in State Archives, some of which are presented below.

Public schools

During the war NSW public schools were a central component of the war effort, engaging in patriotic fundraising activities, functioning as a hub for local recruitment committees, and providing school grounds for rifle club drill purposes[3]. Schools were also some of the first to erect local honour rolls.[4] The July 1915 issue of the Public Instruction Gazette suggested local parents and citizens might “be pleased to provide a Roll of Honour, to be placed on the wall of the school from which any Teacher or old-time Pupil has gone to war, with their names engraved thereon.” The article proposed the boards could be made of varnished wood by manual training students in the school where possible [Fig 1].[5]

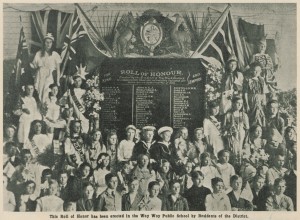

On 22 March 1916, a public meeting was held at Woy Woy Hotel to discuss the erection of a ‘Scroll of Honor’ in the local public school which would display the names of local “lads who had enlisted” [Fig 2],[6] suggesting not only teachers or former students were to be included. The resulting Roll of Honour board was shown in the February 1917 issue of the Education Gazette (formerly Public Instruction Gazette) [Fig 3], surrounded by school children in a patriotic display typical of Australian schools at the time.

- Fig 1: Example of honour roll design, Public Instruction Gazette 1/7/1915. From AK698, 1915, p. 168

- Fig 2: Letter from W S E Hadley re: erection of scroll of honor, 24/3/1916. From NRS 3829, [5/18212], 16/26208

- Fig 3: Woy Woy roll of honor, Education Gazette 1/2/1917. From AK698, 1917, p. 35

In fact, the Gazette demonstrated that there were many creative and even practical interpretations of honour rolls made by, or with the help of, the children of NSW [Figs 4-5]. However, the honour roll was not the only form used to express pride and commemoration in schools.

- Fig 4: South Granville Public School Roll of Honour, Education Gazette 2/9/1918. From AK698, 1918, p. 244

- Fig 5: Tallawang Public School honour roll and first-aid cabinet, Education Gazette, 1/3/1919. From AK698, 1919, p. 59

- Bathurst Public School (WWI) Roll of Honour, 30/09/1954. Digital ID: 15051_a047_000789

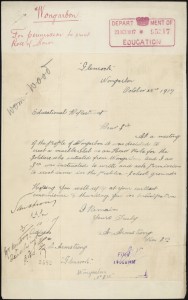

On 22 October 1917, the town of Wongarbon (near Dubbo) requested permission from the Department of Education to erect a “marble slab as an Honor Role [sic] for the soldiers who enlisted” from the town [Fig 6].[7] Permission was granted by the Minister for Education, Augustus James (via Under Secretary Board) later in the month and by April 1919, a monument was standing [Fig 7].[8] Described as a “very fine piece of work”,[9] it was constructed of concrete and marble and was positioned near the old and new school buildings, fronting Railway Street[10] where it could be viewed by passing members of the public.[11]

The monument was central to a dispute in May 1921 when permission was sought to place a captured German machine gun war trophy on the soldiers’ memorial.[12] The initial request was sent on 9 May to the Minister for Lands, William George Ashford, who sent it on with recommendations to new Education Minister, Thomas Mutch. On 31 May the Under Secretary for Education replied that Minister Mutch did “not consider Machine Guns suitable for exhibition in Public Schools.”[13] This decline was also conveyed on the same day to the headmaster of Wongarbon School, W A Oldham, who had supported the town’s belief that there was nowhere else to place the war trophy.[14] However, the message had arrived too late, for despite Oldham’s insistence on awaiting approval from the Minister as the memorial was on Government property, the local citizens had voted to install the gun without departmental permission. It was installed in front of the memorial and unveiled under ceremony by the mother of a local war hero on 24 May (Empire Day) 1921.[15] Minister Mutch requested the name of the person who carried out the work in defiance of instruction, and duly sent a letter to him (Samuel R Armstrong) on 20 July, giving fourteen days to have the trophy removed.[16] This order was complied with by 10 August 1921.[17]

- Fig 6: Letter from A Armstrong re: permission to erect memorial at Wongarbon Public School, 22/10/1917. From NRS 3829, [5/1876.2], 17/65217

- Fig 7: Wongarbon honor memorial, Education Gazette, 1/4/1919. From AK698, 1919, p.74

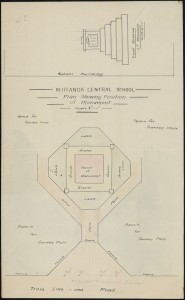

- Fig 8: Miranda Central Public School plan of monument, June 1918. From NRS 3829, [5/16867], bundle A

In June 1918, the residents of Miranda appealed to the Department of Education to grant permission for an amended plan of a monument “in honor of the soldiers who have enlisted from that district” within the grounds of Miranda Central Public School.[18] The design included a bay to allow reading of the name plaque from the passing roadway, the Kingsway [Fig 8],[19] and was unveiled by the Minister for Education, Augustus James at a public ceremony on Saturday 3 August 1918.[20]

By the time of the unveiling, an addition had been made to the memorial in the form of a cement statue of a soldier (shown in above photograph), which had not been in the plan approved by the Department of Education [original plan Fig 8].[21] This statue was the cause of much controversy in the local community, some of whom considered it not “in any way artistic or suitable”.[22]

Towns

Apart from being public expressions of community pride in the enlistment of locals, name-lists displayed while the war was still in play acted as a public ‘scoreboard’ to provide incentive to other members of the related community or organisation to join up.[23]

During the war, NSW recruitment campaigns inspired intensely patriotic involvement from many in the community. Particularly in regional NSW, local people worked in conjunction with the State and Commonwealth governments to supply volunteers for enlistment in the military forces. Many country towns tried to ‘better’ other townships in their area, by offering the greater number of volunteers from their area,[24] and this was embodied in the display of names publicly.

Although honour roll boards had been hanging on the walls of “town halls, schools, churches, lodges, sporting clubs…and other workplaces public and private” since early in 1915,[25] the first war memorial is thought to have been erected in the Balmain town centre in April 1916.[26] Both honour rolls and memorials were usually payed for through the efforts of local fund-raising committees;[27] however some townships also sought assistance from the Government.[28]

In October 1916 the first attempt by the authorities at controlling the construction of memorials was issued by the NSW State War Council via a regulatory amendment to the War Precautions Act,[29] which prohibited patriotic fundraising activity for any purpose (including raising money for monuments), “without approval of a State War Council”.[30] While acknowledging the sentiment and usefulness of memorials in recruitment, the NSW Council believed that the proposed cost of memorials “in some cases running into thousands of pounds” was money better spent on “those who had suffered from the scourge of war”. The cost of producing honour rolls and plaques however, was not considered as significant.[31] This did not stop the building of memorials in NSW, but slowed it.[32]

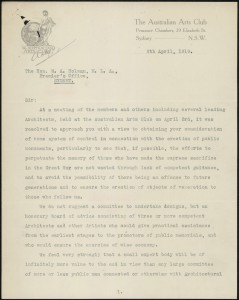

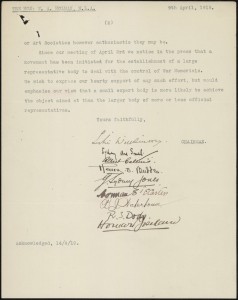

On 3 April 1919, a meeting was held by the Australian Arts Club including “several leading architects” in which the need for a ‘system of control’ was agreed to, in regard to the erection of war memorials throughout the state [Fig 10-11].[33] The meeting attendees wrote to Premier Holman suggesting that a “small expert body” in the form of a board was required, consisting of architects and artists, to ensure that:

“…the efforts to perpetuate the memory of those who have made the supreme sacrifice in the Great War are not wasted through lack of competent guidance, and to avoid the possibility of there being an offence to future generations…”

The idea was that the board would provide advice in both artistic direction and costs, though not to execute designs.[34] Signatories to the letter included artists Sydney Ure Smith and Norman St Clair Carter, as well as architects Bertrand James Waterhouse and George Sydney Jones (grandson of retailer David Jones).

- Fig 10: Letter from Australian Arts Club, 9/4/1919, p. 1. From NRS 12060, [9/4923A], A25/785

- Fig 11: Letter from Australian Arts Club, 9/4/1919, p. 2. From NRS 12060, [9/4923A], A25/785

- Anselm Odling & Sons sculptors ad, Sydney. From NRS 12060, [9/4923A], A25/785

On 2 August 1919, it was announced in the press that the War Memorials’ Advisory Board had been appointed,[35] although it did not appear in the Government Gazette until thirteen days later.[36] The Board sat within the Department of Local Government, under Minister John Daniel Fitzgerald.

The first appointments to the board consisted of a mixture of architects and artists, and one civil engineer:[37]

President:

- John Sulman, architect, president of both National Gallery Trust, and Town Planning Association of NSW

Members:

- Lionel Arthur Lindsay, artist, member of the National Art Gallery Trust

- Gother Victor Fyers Mann, architect, artist, member of the National Art Gallery Trust

- Leslie Wilkinson, Professor of Architecture, Sydney University

- John Job Crew Bradfield, civil engineer, Chief Engineer for the City Railway

- George Sydney Jones, architect, President of the Institute of Architects of NSW

- Arthur F Pritchard, architect, former president of the Institute of Architects of NSW

- Bertrand James Waterhouse, architect, representative of the Institute of Architects of NSW

- John Francis Hennessy, architect, representative of the Institute of Architects of NSW

- William Lister Lister, artist, representative of the Royal Art Society of NSW

- Antonio Dattilo Rubbo, artist, representative of the Royal Art Society of NSW

- John Samuel Watkins, artist, representative of the Royal Art Society of NSW

- Julian Rossi Ashton, artist, representative of the Society of Artists

- Sydney Ure Smith, artist, representative of the Society of Artists

- Norman St Clair Carter, artist, representative of the Society of Artists

- George McRae, NSW Government Architect

- (Vice-President) Robert Smith Dods, architect

The Board’s official duties were limited to “the giving of advice and the furnishing of criticism (if desired); it [could not] undertake to prepare designs, nor furnish estimates of cost”, as per a circular sent to shire and municipal councils throughout NSW on 3 September 1919.[38] Notice of the appointment was also made in the press, and a new clause was inserted into the Local Government Act, 1919 which stipulated that “monuments shall not be erected in public places or public reserves unless and until the design and situation thereof shall have been approved by the Minister.”[39]

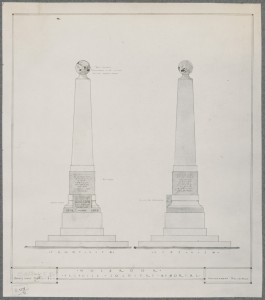

- Holbrook Proposed Soldiers Memorial. Digital ID NRS18195_0000024a

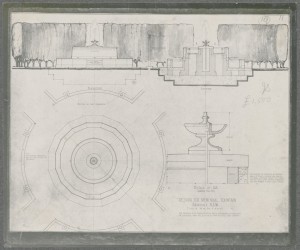

- Design for Memorial Fountain Armidale. Digital ID NRS18195_0000016

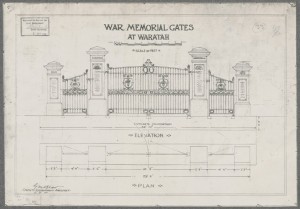

- War Memorial Gates Waratah. Digital ID NRS18195_0000028

In 1920 draftsmen from the Government Architect’s Branch were made available to prepare revised plans based on original entries from non-Government designers.[40] Photographs of their amended design plans can be seen in NRS 18195 Photographs of War Memorials in New South Wales [Government Architect], 1920-1926, amongst original submissions from private architects and members of the public. Some plans include the stamped, signed and dated approval of the Minister for Local Government and/or the approval of the (usually Deputy) Government Architect, as well as pencilled cost estimates.

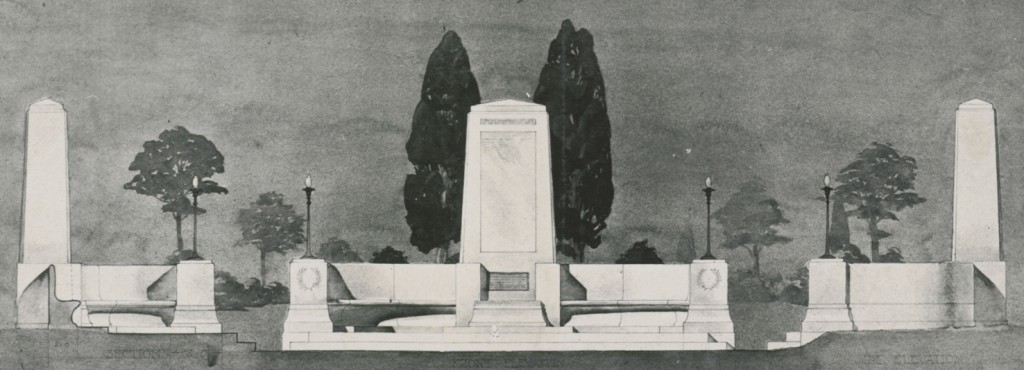

To assist in dealing with “numerous requests for designs”, the Board arranged competitions for certain proposed memorials, with monetary prizes on offer. There were general forms of designs requested by the Board, such as obelisk, column, wall tablet, fountain, and small park shelter; and there were competition designs for specific town War Memorial Committees [see examples above].[41] An example of a town competition run was that of Temora, for which the winner Bengt Tojkander (who also won the competition for the Corowa memorial)[42] was announced in the press on 21 December 1920.[43] Tojkander’s design can be seen along with other submissions within the NRS 18195 photographed plans [see examples below].

- Temora memorial Bengt Tojkander design. From NRS 18195

- Temora War Memorial Competition. Digital ID NRS18195_000005

- Competition design War Memorial Temora. Digital ID NRS18195_000006

- Soldiers Memorial Temora. Digital ID NRS18195_000007

In the first year of the Board’s existence, the Minister for Local Government approved eighteen out of twenty-nine applications, and rejected eleven.[44] One element of a memorial that may have been rejected if the Board had existed at the time of construction, was the statue of the Miranda Central Public School memorial. On 22 March 1920, the Miranda Parents’ and Citizens’ Association had written to the Department of Local Government asking for the removal of the statue, leaving the original design intact.[45] President of the War Memorials’ Advisory Board, John Sulman, inspected the monument himself and agreed that the statue was “very unsatisfactory” from an artistic perspective. He suggested that “it be removed and a war relic such as a large trench mortar, or small field gun” replace the statue atop the pedestal [Fig 12].[46] The Department of Education’s perspective remained that it was not suitable for weapons to be placed within school grounds [Fig 13], and the statue was removed at the cost of that Department[47] in November 1920.[48]

An image of the Miranda statue was used by the War Memorials’ Advisory Board in the Department of Local Government’s 1920 Bulletin No. 4, ‘War Memorials’, as an example of why the Board was required in the first place.[49]

- Fig 12: Miranda memorial statue report, 5/5/1920. From NRS 3829, [5/16867], Bundle A

- Fig 13: Miranda memorial statue removal, 3/9/1920. From NRS 3829, [5/16867], Bundle A

- Fig 14: Wagga Wagga soldiers’ memorial approved. From NRS 18195

On 6 May 1921 in recognition that its purpose according to the act could include non-war-related monuments, the Board was ‘reconstructed’ and the name changed to be the Public Monuments Advisory Board.[50]

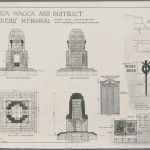

In that year the town of Wagga Wagga had an amended memorial cenotaph design approved by the Board to include the names of locals who had died in the war. The Wagga memorial is an example shown in the NRS 18195 plans, of the variations in design and the changes made throughout this approval process – changes seemingly made sometimes after an approved design may have been decided upon. The approved (stamped) design is shown above[Fig 14], as opposed to another submission [Fig 15] which is actually closer in design to the structure that was built [see Fig 17]. In addition to the cenotaph, a 1926 design for a memorial arch was approved to include the names of all local servicemen and women who served during the war [Fig 16], and built near to the first memorial in what became known as the Victory Memorial Park.[51]

- Fig 15: Wagga Wagga soldiers’ memorial alternate. From NRS 18195

- Fig 16: Wagga Wagga soldiers’ memorial arch. From NRS 18195

- Fig 17: Wagga memorial park (n.d.). Digital id: 12932-a012-a012X2442000126

Related:

Plans for war memorials

In remembrance

Conscription (History Week 2015 webpage)

William Arthur Holman (History Week 2015 webpage)

Related external links:

References

[1] Inglis, KS, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Melbourne University Press, 1998, p. 106.

[2] Ibid, p. 108.

[3] State Archives New South Wales: Department of Education; AK698 Education Gazette, 1915, p. 48.

[4] McKernan, Michael, The Australian people and the Great War, William Collins Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1980, p. 56.

[5] AK698, 1915, p. 168.

[6] AK698, 1917, p. 35.

[7] SANSW: Department of Education; NRS 3829 School files, Wongarbon Public School [5/17156.2], 17/95317.

[8] AK698, 1919, p. 74.

[9] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 19/77731.

[10] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 19/77731 enclosing ‘Block Plan’, 16/2/1919.

[11] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 19/77731 enclosing 19/32047.

[12] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 21/62779.

[13] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 21/62779 enclosing 21/19697.

[14] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 21/62779 enclosing 21/52404.

[15] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], enclosing 21/40265.

[16] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], enclosing B21/25941.

[17] NRS 3829, [5/17156.2], 21/62779.

[18] NRS 3829, [5/16867 A], Miranda Public School, 1918-1939.

[19] Handley, M, and Hewitt, S, Service and Sacrifice: Sutherland Shire Memorials 1914-1918, Sutherland Shire Council, 2015, p. 11.

[20] “UNVEILING OF HONOR ROLL.” St George Call, 3 August 1918, p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162770203.

[21] Handley and Hewitt, p. 12.

[22] NRS 3829, [5/16867 A], 20/81049 enclosing 20/34571.

[23] McKernan, p. 187.

[24] Ibid, p. 187.

[25] Inglis, KS, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Melbourne University Press, 1998, p. 106.

[26] Ibid, p. 108.

[27] Ibid, p. 123.

[28] SANSW: Premier’s Department;Premier’s Department; NRS 12060 Letters received [9/4926B], B25/285.

[29] Inglis, p. 120.

[30] NRS 12060 [9/4745], A17/4293 enclosing A17/496.

[31] “War Memorials.” The Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser, 13 July 1917, p. 7. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article121278115.

[32] Inglis, p. 120.

[33] NRS 12060 [9/1945A] A25/785, letter from The Australian Arts Club, 9/4/1919.

[34] Ibid.

[35] “WAR MEMORIALS.” Evening News, 2 August 1919, p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116083375

[36] Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 1919, Vol. 3, p. 4525, Friday 15 August 1919.

[37] Parliamentary Papers, Second Session 1920, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1919-1920, p. 17.

[38] SANSW: Department of Local Government; NRS 9613, Departmental circulars, 27 February 1915-12 September 1946, [3/3177], Circular No.305, ‘War Memorial Advisory Board’, p. 311.

[39] Parliamentary Papers, Second Session 1920, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1919-1920, p. 17.

[40] Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1921, p. 26.

[41] Parliamentary Papers, Second Session 1920, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1919-1920, p. 17-18.

[42] Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1921, p. 26.

[43] “WAR MEMORIAL COMPETITION.” Sydney Morning Herald, 12 December 1920, p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16880891

[44] Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1921, p. 26.

[45] NRS 3829, [5/16867 A], 20/81049.

[46] NRS 3829, [5/16867 A], 20/81049 enclosing 20/34571.

[47] NRS 3829, [5/16867 A], 20/81049.

[48] Handley and Hewitt, p. 14.

[49] Inglis, p. 498.

[50] Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Vol. 3, Department of Local Government Annual Report, 1921, p. 25.

[51] “Victory Memorial Gardens”, Wagga Wagga City Council, 2012, Retrieved from http://www.waggawaggaaustralia.com.au/visitor-information/about-wagga-wagga/history/historic-events-and-locations/victory-memorial-gardens/