How the battle was waged

Conscription propagandaThis webpage was developed as part of State Archives’ contribution to History Week 2015.

Newspapers

Newspapers were one of the main methods used to voice opinions on conscription. In New South Wales, the mainstream press was mostly pro-conscription, as were publications such as ‘The Soldier’. (1) The most vocal opposition came from those publications that were linked to trade unions or workers, such as the Labor Party’s ‘The Australian Worker’, the Industrial Workers of the World’s ‘Direct Action’, and the Amalgamated Miners’ Association’s ‘Barrier Daily Truth’. (2) During the war, the editors of all three papers were charged under the War Precautions Act either for sedition or remarks prejudicial to recruiting. (3)

- [Fig. 1] The Soldier. From NRS 313 [7/5546 letter 16/6921].

- [Fig. 2] The Soldier, p.2. From NRS 313 [7/5546 letter 16/6921].

- [Fig. 3] Direct Action, December 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7442 letter 16/40328].

- [Fig. 4] Direct Action, December 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7442 letter 16/40328, p.2].

- [Fig. 5] Direct Action, December 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7442 letter 16/40328, p.3].

- [Fig. 6] ‘Guilty, or not guilty’, The Australian Worker. From NRS 313 [7/5546 letter 16/6921].

Pamphlets, letterheads and other printed material

Printing firms throughout New South Wales may well have benefited from the increased business as they were called upon to produce a variety of printed items for the various conscription causes. Many groups had their own letterheads, which meant that every letter sent was also a vehicle for propaganda.

- [Fig. 7] No-conscription campaign letter, 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7392 16/229].

- [Fig. 8] National Referendum Campaign Committee, 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7392 letter 16/229].

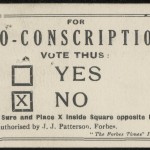

Handbills, posters, stickers and pamphlets (such as ‘The War Trust’) were also printed and distributed by some of the organisations. (4) On the day of the first plebiscite, police confiscated a ‘How to vote No’ card from J J Patterson, the President of the Anti-Conscription League in Forbes, who was giving the cards out to voters. The police claimed that he had breached the Military Referendum Act, but in fact the card complied with the regulations regarding electoral advertisements and no action was taken. On the same day, Forbes police attempted to seize a ‘Vote No’ placard off the back of a truck. The placard did contravene the regulations, but was destroyed before police could retrieve it. (5)

- [Fig. 9] Anti conscription handbill, 1916. From NRS 10923 [7/5592 letter 16/28832].

- [Fig. 10] Anti conscription League of Australasia handbill. From NRS 10923 [7/5593 F1].

- [Fig. 11] How to vote card, 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7441 letter 16/33387].

Public meetings

The main alternative to newspapers was public meetings. Each Sunday, tens of thousands of Sydney-siders would congregate at the Domain to listen to the various speakers. Other Sydney locations were also used, such as Bathurst Street, Sussex Street, Paddington and Woollahra. Groups such as the Industrial Workers of the World, the Universal Service League, and the Political Labor League would bring in wagons and lorries to use as platforms, from which they would pronounce their views. (6) The IWW claimed to have held 120 Sunday afternoon meetings, 240 hall lectures, and over 300 outdoor street meetings in Sydney alone between August 1914 and October 1916. (7) Similar, although much smaller, meetings were also held at various rural locations such as Broken Hill, Bulli and Narrabri. (8)

As the debate over conscription intensified, the meetings became larger and more emotionally charged. On 13 August 1916, the police estimated that 80 000 people were in attendance at the Sydney Domain as the Political Labor League began to espouse its views against conscription. Hecklers in the crowd attempted to disrupt the speakers with interjections and ‘counting out’, and several rushes were made at the platform, causing a great deal of jostling and pushing to occur. The meeting was abandoned due to the risk of injury, however the crowd then moved straight to the IWW platform where a repeat of the same situation eventually caused their meeting to be closed down as well. (9)

Immediately after the event, the Metropolitan Superintendent of Police sent a memo to the Chief Secretary in which he strongly recommended that further meetings be stopped due to ‘the terrific surges of the mass of people’ moving from one speaker to another which, given the ‘inflamed minds’ of the people, could lead to riots. The Chief Secretary responded by immediately suspending all meetings to do with conscription. (10)

- [Fig. 12] Report from Detective 1st Class N Moore, 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7442 letter 16/40328, p.1].

- [Fig. 13] Report from Detective 1st Class N Moore, 1916. From NRS 905 [5/7442 letter 16/40328, p.2].

The PLL and other unionists were incensed by what they saw as restriction of freedom of speech, and large gatherings were organised in the Domain in protest. However by 1 October the Chief Secretary had relented and conscription-related meetings were being held there again, but permission had to be sought before a meeting could be held. (11)

The government kept a close eye on what was being said by the speakers. Plain clothes police were rostered on to attend the meetings, taking shorthand notes of what was said with a view to identifying seditious remarks or other potential breaches of the War Precautions Act. These notes were then sent back in typed reports to the Chief Secretary for action. (12)

New South Wales decides

On 28 October 1916 Australia cast its vote. Even the soldiers at the front were given the opportunity to make their voice heard in what was called the ‘Anzac vote’. (13) However the results were not as the Premier or the Prime Minister had hoped. In New South Wales, 474 544 people, or 57% of voters, were against conscription. Nationally, it was a 52% ‘no’ vote. (14)

Some towns and suburbs had a majority vote either way. For example, in Mosman the ‘yes’ vote was 81%, while in Broken Hill, 70% of constituents voted no. However places such as Bexley, Naremburn, Gosford and Nowra were literally split down the middle, with only a handful of votes the difference. (15)

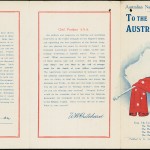

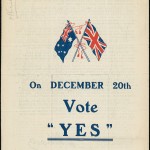

The Australian Government did not give up on the idea of conscription after the first plebiscite, holding a second plebiscite on 20 December 1917. Despite more emotional pleas for conscription from key leaders in government [Fig. 14-15], the ‘no’ vote was even higher the second time around. (16) It was a clear message from the people of New South Wales and Australia.

- [Fig. 14] Australian Natives’ Association of NSW pamphlet, 1915. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7546, p.1]. Pamphlet

- [Fig. 15] Australian Natives’ Association of NSW pamphlet, 1915. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7546, p.2].

- [Fig. 16] Vote Yes leaflet. From NRS 12060 [9/4762 letter 15/7546, p.4].

The conscription debate caused great division in the community both before and after the plebiscites. In the city there was more chance for breathing space between those with opposing views, but in small rural towns, where there was only one pub and one general store, locals had little choice but to rub shoulders with each other.

One Friday afternoon in October 1916, a few of the locals were having a beer at the Commercial Hotel in Goolagong (now Gooloogong) in Central Western NSW. The question, ‘Are you a conscriptionist?’ was all it took to set things off. After the brawl was over, Messrs Haydon, McKenzie, Edmunds and Ryan all found themselves summonsed to the Eugowra Court of Petty Sessions, where the magistrate likened them to a ‘pack of dingoes’. (17) They faced various charges including assault, riotous behaviour, and threatening words such as ‘I’ll have you, you coot conscriptionist’.

- [Fig. 17] Police summons, George Haydon. From NRS 2981[38/31].

- [Fig. 18] Police summons, John Haydon. From NRS 2981[38/31].

- [Fig. 19] Police summons, William James Edmunds. From NRS 2981[38/31].

- [Fig. 20] Police summons, Thomas Ryan. From NRS 2981[38/31].

- [Fig. 21] Police summons, Samuel McKenzie. From NRS 2981[38/31].

- [Fig. 22] Police summons, Thomas Haydon. From NRS 2981[38/31].

In Nyrang Creek, farmer Robert Newham was forced to place an advertisement in the local paper to defend his reputation and dispel rumours that he was in favour of conscription. In Murwillumbah, Mr D J Gillies placed an advertisement to propose a resolution that all anti-conscriptionists should refuse to deal, trade or associate with any person who advocated conscription. Incidents like these were repeated around the state even after the plebiscites were over. (18)

- [Fig. 23] Police letter, November 1916. From NRS 313 [7/5545 letter 16/6538].

- [Fig. 24] Public notice, The Tweed Call, 1916. From NRS 313 [7/5545 letter 16/6538].

By the end of the war, Australia and South Africa were the only two Allied countries that had not introduced compulsory service. (19)

Conscription was a spectre that had been temporarily put to rest, but it would raise its head again during the next World War.

Related

References

(1) ‘Country Press Favor Conscription’, Canowindra Star and Eugowra News, 20 October 1916, p. 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118103598; Gilchrist, Catie, ‘Socialist Opposition to World War I’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2014, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/socialist_opposition_to_world_war_i ,(accessed 17 August 2015).

(2) State Archives New South Wales: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Letters received [5/7439] 16/37686, Report of Inspector General of Police on anti-conscription movement in Broken Hill 20/8/1916.

(3) SANSW: Police Department; NRS 10923, Special Bundles [7/5588]; ‘W. D. Barnett’s Conviction’, Barrier Miner, 18 December 1916, p. 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45410643.

(4) Beattie, Bill, ‘Memoirs of the I.W.W.’, Labour History, 13 (1967): 33-39, https://libcom.org/files/Memoirs%20of%20the%20I.W.W.pdf, (accessed 3 August 2015); SANSW: Government Printing Office; NRS 4415, Correspondence with other Government departments [1/193] 15/D4528, ‘The Truth About German Atrocities’.

(5) Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth), s.180; Military Service Referendum Act 1916 (Cth), s.12(2); NRS 905 [5/7441] 16/38387, Report from Inspector General of Police; NRS 905 [5/7441] 16/38386, Letter from Constable 1st Class James Jenkinson, Police Station Forbes.

(6) NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37727, Report from Sergeant Thomas Robertson re: meetings held in the Sydney Domain; NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37666, Letter from Inspector General of Police re: Anti-Conscription meeting in the Sydney Domain; NRS 905 [5/7392] 16/229, Report from Metropolitan Superintendent re: Conscription meetings held in No. 10 Division.

(7) ‘Spasms’, Direct Action, 24 Feb 1917, Issue No. 110, , p.4, http://www.jura.org.au/files/jura/DirectAction-No110-24Feb1917.pdf.

(8) NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37666; NRS 905 [5/7441] 16/38384, Report on Narrabri anti-conscription meeting; NRS 905 [5/7439] 13/37686, Report from Inspector General of Police re: anti-conscription movement at Broken Hill.

(9) Beattie, Bill, p.37; NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37666.

(10) NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37666.

(11) ‘In Australia’, Barrier Miner, 4 September 1916, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45427599; ‘Meeting in the Domain’, Barrier Miner, 2 October 1916, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45411866; NRS 905, [5/7392] 16/229, Letter from National Referendum Campaign Committee.

(12) NRS 905 [5/7439] 16/37666 & 16/37727.

(13) ‘Conscription Referendum’, Swan Hill Guardian and Lake Boga Advocate, 29 March 1917, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91132991.

(14) Commonwealth of Australia. (2011). Parliamentary Handbook for the 42nd Parliament, Part 5: Referendums and Plebiscites, pp. 398-399, http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Parliamentary_Handbook (accessed 14 August 2015).

(15) NRS 905 [5/7554] 16/6859, Military Service Referendum, 28th October 1916, State of New South Wales

(16) Commonwealth of Australia, pp. 398-399.

(17) ‘Eugowra Police Court’, Canowindra Star and Eugowra News, 3 November 1916, p. 6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118103687; SANSW: Eugowra Court of Petty Sessions; NRS 2981, Depositions [38/31] Summons Case No. 51/1916-63/1916.

(18) ‘Advertising’, Canowindra Star and Eugowra News, 27 October 1916, p. 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118103604; ‘An Interesting Assault Case’, Leader, 27 November 1916, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article117818124; SRNSW: Department of Attorney General and of Justice; NRS 313, Letters received [7/5545] 16/6558, Letter from Inspector General of Police re: notice in Tweed Call newspaper; ‘Alleged Assault At Teven’, The Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser, 9 January 1917, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article121278974.

(19) Turner-Graham, E. (2009). ‘Conscription, World War I, 1914-1918’, in Museum Victoria Collections, http://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/articles/2823, (accessed 21 August 2015).