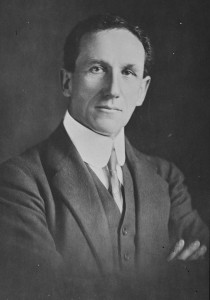

William Arthur Holman

1916: Crisis point over conscription- Premier Holman addresses the Waratahs in Sydney, December 1915. NRS 4481 MS3658P.

- Premier Holman addressing a crowd at Botanic Gardens Centenary celebrations, June 1916. NRS 4481, MS3931P.

This webpage was developed as part of State Archives contribution to History Week 2015.

From cabinet maker to premier

William Arthur Holman was born in London on 4 August 1871 and migrated to Australia with his family in September 1888. Holman had already served an apprenticeship in London as a cabinet maker.(1)

The depression of the early 1890s that was felt across Australia had a profound influence on Holman.[Fig. 1] Michael Hogan, in his biography on Holman, goes so far as to call the depression “a radicalising experience” that provided an ideological and socialist education for Holman that influenced his politics for over twenty years.(2) Holman joined such groups as the School of Arts Debating Society, the Socialist League and the Labor Electoral League, the forerunner of the Labor Party. (3) He also gained first hand union experience as a Secretary of Railways and Tramways Employees Association, as a delegate representing the furniture trades to the Trades and Labor Council and as an organiser for the Australian Workers’ Union. (4)

For a time, Holman also worked as a journalist, becoming one of the directors of the Daily Post, which in 1895, was an attempt to publish a labour leaning newspaper. Due to a lack of financial backing and poor financial management the Daily Post only lasted four months.(5) Holman, along with four other directors of the newspaper, were charged with conspiracy to defraud and served two months in Darlinghurst Gaol before their conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court. (6)

After several attempts at standing for parliament, Holman eventually won the seat of Grenfell in the central west of New South Wales in 1898. This event seemed to have huge sentimental significance for him, as his daughter, born in 1903, was named Portia Grenfell Holman. Holman entered Parliament as a well-established Labor figure, with nearly a decade of experience at the grass-root level of organising policy and political campaigning. He also had connections to the Labor Party Central Executive, of which he had been a member in 1897. (7)

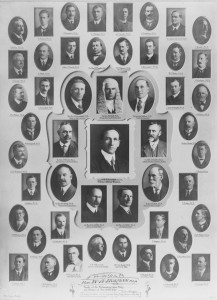

[Fig. 2] Premier Holman and Labor Party Members of the Legislative Assembly, August 1914. NRS 4481, ST13302P.

For the first few years as a Member of the Legislative Assembly Holman learned the parliamentary ropes. He also decided that in the future the Labor Party would benefit from legal expertise, so he read for the bar.(8) Holman was admitted to the bar on 31 July 1903 and ran his own legal practice as a barrister.(9) He focused mainly on industrial, constitutional and common law cases in his practice.(10)

In 1910, the Labor Party, under the leadership of James McGowen, won the election and became the first Labor government in NSW. Holman, already the Deputy Leader, was sworn in as Attorney-General. When McGowen was forced to resign, Holman took over as the 19th Premier of New South Wales, on 30 June 1913.[Fig. 2] In a little over a year Australia was at war.

1916 – War time crisis

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 created new political and financial demands for the Labor Government. For Holman in particular, the war was also a challenge to his pacifist ideals. In a letter to the NSW Political Labor League Executive in August 1916, Holman laid out his “pronounced and declared anti-militarist” pedigree, as he termed it. (11) Holman claimed that during the Boer War he was one of the founders of an anti-war league and he also went on to join a Peace Society founded by Rose Scott. (12) For Holman though, the defence of Australia and the British Empire created a situation where his earlier pacifist beliefs could be put aside for the time being. This turnaround in beliefs can be summed up in his own words:

I am of opinion that only by a complete and crushing victory can militarism, conscription and the other evils against which I have struggled all my life, be avoided. I am convinced that either a defeat of the Allies Armies or a termination of hostilities with honors divided – that is, anything short of a crushing victory in the part of the Allies – will precipitate all of them in a permanent form. (13)

Holman threw his great capacity for hard work and organising flair into supporting the war effort. For a man who professed ‘anti-militarist’ beliefs, he was now prepared to use the machinery of government of NSW to support the war. Holman quickly pledged his support, and that of the state, to the Federal Government. [Fig. 3] He promised “assurances of the fullest possible co-operation in the present crisis” to Prime Minister Cook. (14) Holman also instituted a political truce with the Leader of the Opposition, Charles Wade, with both sides of the House agreeing not to introduce any controversial legislation for the period of the war. (15)

- [Fig. 3] Letter to PM Cook from Premier Holman, August 1914. NRS 12060 [9/4692 letter 14/4887, p.1].

- [Fig. 4] List of officers of Universal Service League, NSW Branch. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7337, p.1].

- [Fig. 5] Universal Service League Manifesto. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7337, p.2].

Such was Holman’s commitment to the war effort that he supported recruitment campaigns across the State. He joined the Universal Service League [Fig. 4-5] as an executive member, along with fellow parliamentarians John Cann, Arthur Griffith, George Black, David Hall, William Ashford and Charles Wade.(16) The League’s first duty was to campaign to send more men to the Front through “universal compulsory service at home or abroad in the battlefield.”(17)

Holman clashes over conscription

During 1916 Holman had two major clashes with the Political Labor League (from 1918 the Political Labor League became known as the Australian Labor Party, NSW Branch) over conscription. The issue of conscription proved as much of a divisive issue within the ranks of the Labor Party as it did for Australian society in general. The war and conscription also proved to be a turning point for Holman to leave the Labor Party behind him.

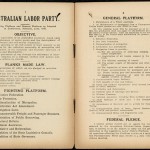

The first clash between Holman and the Political Labor League occurred during its Annual Conference, held in Sydney in May 1916.[Fig 6-7] The Executive was keen to clarify the party standpoint in relation to conscription and after much debate the following resolution [Fig. 8] was passed:

[The Political Labor League] pledges itself to oppose by all lawful means conscription of human life for military service abroad. (18)

The vote on the conscription resolution took place on a night when Holman, an executive member, was absent from the Conference. (19) The Executive also refused to endorse any Labor candidate that supported conscription, putting the Executive at odds with the Premier and his ministers.

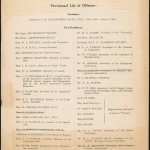

- [Fig. 6] Australian Labor Party, NSW Political Labor League executive, April 1916. From NRS 12060 [9/4791 letter B18/2296, p.1].

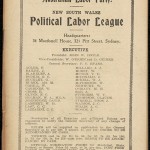

- [Fig. 7] Australian Labor Party fighting platform and general platform from June 1915. From NRS 12060 [9/4791 letter B18/2296, pp2-3].

- [Fig. 8] PLL Executive conscription resolution, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252 letter B16/3853, p.2].

In response to the passing of the conscription resolution, Holman wrote to the Political Labor League to voice his concerns:

So far as the resolution is valid, its only effect is, in my judgement, to place the New South Wales Executive under the responsibility of determining whether action is to be taken of a character hostile to Labor candidates who are convinced of the necessity for Compulsory Service.(20)

Holman, and most members of his Cabinet, were still willing to back the necessity of conscription. (21) In response, the Political Labor League Executive passed a censure motion against Holman and Holman resigned as Premier to the Labor Caucus.(22) Within one day though, the Executive had backed down and Holman remained on as Premier.

- [Fig. 9] Governor Gerald Strickland. From NRS 4481 MS5182P.

- [Fig. 10] Draft minute to Governor Strickland from Premier Holman, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252, p.1].

- [Fig. 11] Draft minute to Governor Strickland from Premier Holman, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252, p.2].

- [Fig. 12] Draft minute to Governor Strickland from Premier Holman, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252, p.3].

- [Fig. 13] Draft minute to Governor Strickland from Premier Holman, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252, p.4].

- [Fig. 14] Draft minute to Governor Strickland from Premier Holman, May 1916. From NRS 12172 [4/6252, p.5].

This confrontation earned Holman the ire of the NSW Governor, Gerald Strickland.[Fig. 9] Technically ministers could only resign to the governor. Strickland, in a letter to Andrew Bonar Law, the British Colonial Secretary,states that he “was not prepared to appear to acquiesce in a real or alleged change in the constitutional procedure as regards the resignation of Ministers.” (23) Holman apologised to the Governor and although appeased, their relationship never fully recovered.[Fig. 10-14] Holman’s superb political manoeuvring to stay in power had left him offside with the Labor Party and the Governor. In the next six months this situation worsened.

Fallout from plebiscite vote

The second more serious fallout between Holman and the Political Labor League occurred in the wake of the conscription plebiscite. When Prime Minister WM Hughes returned from a tour of the Western Front in August 1916, he announced plans for a plebiscite (non-binding referendum) on the conscription issue to be held on 28 October 1916. Holman and Hughes campaigned for a ‘Yes’ vote in the plebiscite, which brought both men into conflict with the Labor Party Executives.

- [Fig. 15] Australia must do her share recruitment flyer. From NRS 12060 [9/4718 letter A16/2303, p.1].

- [Fig. 16] Holman’s message in the Australian Natives’ Association of NSW flyer, 1915. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7546, p.1].

- [Fig. 17] Recruitment cartoon from the Australian Natives’ Association of NSW flyer, 1915. From NRS 12060 [9/4705 letter 15/7546, p.2].

Holman campaigned extensively throughout the State in support of compulsory military service. The rhetoric of his speeches and messages from mid-way through 1915 can be viewed as laying the groundwork for compulsory military service. In a speech on 2 August 1915 Holman stated:

We are to-day fighting for complete and final lasting victory. That can only be obtained by the co-operation of all.(24)

This speech was printed up as a flyer to be distributed throughout the state.[Fig. 15] In another publication from the Australian Natives’ Association of NSW [Fig 16-17], Holman’s message again reiterates the themes of service and equitable contribution:

Australia’s contributions to the fighting strength of the Allies, though magnificent in quality, are not yet entirely representative of our national powers. (25)

In September 1916, in the middle of plebiscite campaigning, the Political Labor League Executive, acting on the May resolution, withdrew endorsement of Holman and his fellow Labor Ministerial colleagues. Holman viewed this course of action as suicidal for the Labor Party.(26) For Holman, the Labor Party was giving away its majority in the House, with no guarantee that the party would win the next election.(27)

When the final votes of the plebiscite were counted in October 1916, the ‘No’ vote had won. In NSW 57% of the vote was on the negative side.(28) This was a crushing defeat for both Holman and Hughes. After the plebiscite vote, the Labor Party elected Ernest Durack as the new leader to replace Holman. They had the support of 22 members of Caucus while Holman maintained the support of 22 fellow members. There were also three Members (Arkins, Carmichael and Fern) on active service.(29)

In the past when Holman had run-ins with the Political Labor League, compromises had been reached. Now it seemed Holman no longer had the patience and labour zeal. While Durack and the Labor Party called for Holman to resign as Premier, Holman once again out manoeuvred his parliamentary colleagues. He entered into negotiations with the Leader of the Opposition, Liberal-Progressive party leader Charles Wade, and a new Nationalist coalition was formed. The new party contained five Holman supporters and ex-members of the Labor government (Holman, Hall, Ashford, Grahame and Fitzgerald), five Liberals (Fuller, Ball, Fitzpatrick, James and Garland), along with George Beeby from the Progressive Party.(30) This new administration was sworn in on 15 November 1916 and Labor were relegated to the opposition benches.[Fig. 18]

Governor Strickland again believed that Holman had acted in an unconstitutional manner by continuing as Premier with a Nationalist coalition rather than with the support of the Labor Party. Strickland also refused to continue to work with Holman and his Nationalist coalition.(31) Holman sought clarification of his position from the British Government, and not surprisingly, Whitehall sided with Holman and the new government was sworn in. Strickland now found himself in an untenable situation, and when Holman asked for Strickland to be recalled, he went on extended leave the following year.(32)

- [Fig. 18] Order of precedence of ministers in new Nationalist coalition, November 1916. From NRS 4541 [7/1670 letter 16/806].

- [Fig. 19] Holman cartoon, from The Worker, 9 November 1916. From NRS 12060 [9/4754 letter B17/804].

- [Fig. 20] Misalliance cartoon featuring Holman, Fuller and Beeby, 16 November 1916. NRS 12060 [9/4754 B17/804, The Worker].

Holman continued his stranglehold on power following the election in March 1917. His Nationalist coalition [Fig. 19-20] garnered enough votes to win 52 of the 90 seats, while Labor only won 33 seats.(33) Holman departed for Europe and America and did not return to Australia until October. On his return, Holman found himself caught up again with the continuing conscription debate. Hughes, also expelled by the Labor Party and now head of a National Federal Government, called for another plebiscite vote on 20 December 1917. Even though Holman had thought the conscription issue had been laid to rest and felt betrayed by Hughes, he started campaigning for a “Yes’ vote again.(34) Travelling throughout the state Holman again demonstrated his oratory skills with punchy one-liners:

You must meet conscription with conscription or you must perish in the struggle.

Why should other nations fight under conscription to protect us? (35)

![Private Holman newspaper cutting, Sunday Times, 25 November 1917. From NRS 12172 [4/6252].](http://nswanzaccentenary.records.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/NRS121724_6252-Sunday-Times_clipping-150x150.jpg)

[Fig. 21] Private Holman newspaper cutting, Sunday Times, 25 November 1917. From

NRS 12172 [4/6252].

The 1917 plebiscite was defeated, just as in the previous year. Holman maintained power but increasingly his government was ineffectual and personal attacks [Fig. 21] on Holman increased.(36) In the 1920 election Holman was defeated and retired from NSW politics.

Holman was the Premier of New South Wales for six years and nine months, spanning the entire period of World War I. He was, in fact, the only state leader to remain in office during the war. His legacy though, has been coloured by the events that occurred in 1916. Holman, a supporter of conscription for overseas service, left behind his Labor roots and formed a new Nationalist government. Holman was forever caught between the Labor Party, who viewed him as a traitor, and the Nationalists, who didn’t quite trust him or his background.

Final years

Holman returned to his legal practice after his election defeat, becoming King’s Counsel in 1920.(37) He returned to the political campaign trail in 1926, acting as campaign director for the NSW National Party. In 1931 Holman was elected to the Federal seat of Martin, which he held until his death on 5 June 1934, aged sixty-three. Holman was remembered for his dauntless energy, great oratory talents, skill as a political tactician and dedication to public service throughout his life.(38)

Related

References

(1) Nairn, Bede, “‘Holman, William Arthur (1871–1934)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/holman-william-arthur-6713/text11589, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online 24 August 2015

(2) Hogan, Michael, “William Arthur Holman (30.06.1913 – 12.04.1920)”, The Premiers of New South Wales 1856-2005, Vol. 2 1901-2005, ed. David Clune and Ken Turner, Sydney, Federation Press, 2006, p. 118

(3) Parliament of New South Wales: Mr William Arthur Holman, http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/parlment/members.nsf/0/20F95DAB942C215DCA256CB600144CE4, accessed on 20 August 2015

(4) Hogan, p. 118

(5) Nairn

(6) NSW State Archives: Clerk of the Peace; NRS 847, Registers of criminal cases tried at Sydney Quarter Sessions, Case #5, March 1896

(7) Parliament of New South Wales: Mr William Arthur Holman

(8) Nairn

(9) New South Wales Law Almanac for 1904, http://lawalmanacs.info/almanacs/nsw-law-almanac-1904.pdf, accessed on 18 August 2015

(10) Parliament of New South Wales: Mr William Arthur Holman

(11) NSWSA: Premier’s Department; NRS 12060, Letters received, [9/4736], B16/4153

(12) Ibid

(13) Ibid

(14) NRS 12060, [9/4692], 14/4887

(15) Hogan, p. 129

(16) NRS 12060, [9/4705], 15/7337

(17) Ibid

(18) NRS 12172, Unregistered papers and pamphlets. [4/6252], B16/3853

(19) NRS 12060, [9/4736], B16/4153

(20) Ibid

(21) Hogan, p. 130

(22) Hogan, Michael, Labor Pains: Early Conference and Executive Reports of the Labor Party in New South Wales, Vol. 3, Sydney, Federation Press, 2008, p. 4

(23) NSWSA: Governor; NRS 4541, Despatches from other Governors, [7/1668A], 16/392

(24) NRS 12060, [9/4718], A16/2303

(25) NRS 12060, [9/4705], 15/7546

(26) NRS 12060, [9/4736], B16/4153

(27) Ibid

(28) Hogan, p. 131

(29) Hogan, Labor Pains, p. 6

(30) Hogan, pp. 132-33

(31) Hogan, Michael, “Sir Gerald Strickland, Count della Catena (14 March 1913 – 27 October 1917)”, The Governors of New South Wales 1788-2010, ed. David Clune and Ken Turner, Sydney, Federation Press, 2009, p. 439

(32) Ibid, pp. 440-42

(33) Hogan, p. 133

(34) Hogan, p. 134

(35) NRS 12172, [4/6252], Daily Telegraph cutting, 28-11-17

(36) Hogan, p. 134

(37) New South Wales Bar Association: Silk Appointments, http://www.nswbar.asn.au/docs/webdocs/silk_all.pdf, accessed on 18 August 2015

(38) “Mr Holman”, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June 1934, p. 12, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17081061, accessed on 20 August 2015